Ironwork

Metallic structural elements

The Use Of Iron In Crete Through The Ages

With the discovery of iron, man began to work and use it to make the tools necessary to his survival. Thus people learnt to handle and exploit this raw material, constantly creating new techniques.

The Ancient Greeks considered metallurgy an important art, sacred to gods and demigods. Hephaestus was the god of “fire, which works for the transformation of metals”, while his sons, the Cabeiri, were “spirits of fire and metalworking”.

During the Second Byzantine Period (961-1204), after two centuries of decay new cultural elements and technologies were brought to Crete, including that of metallurgy (Byzantine motifs).

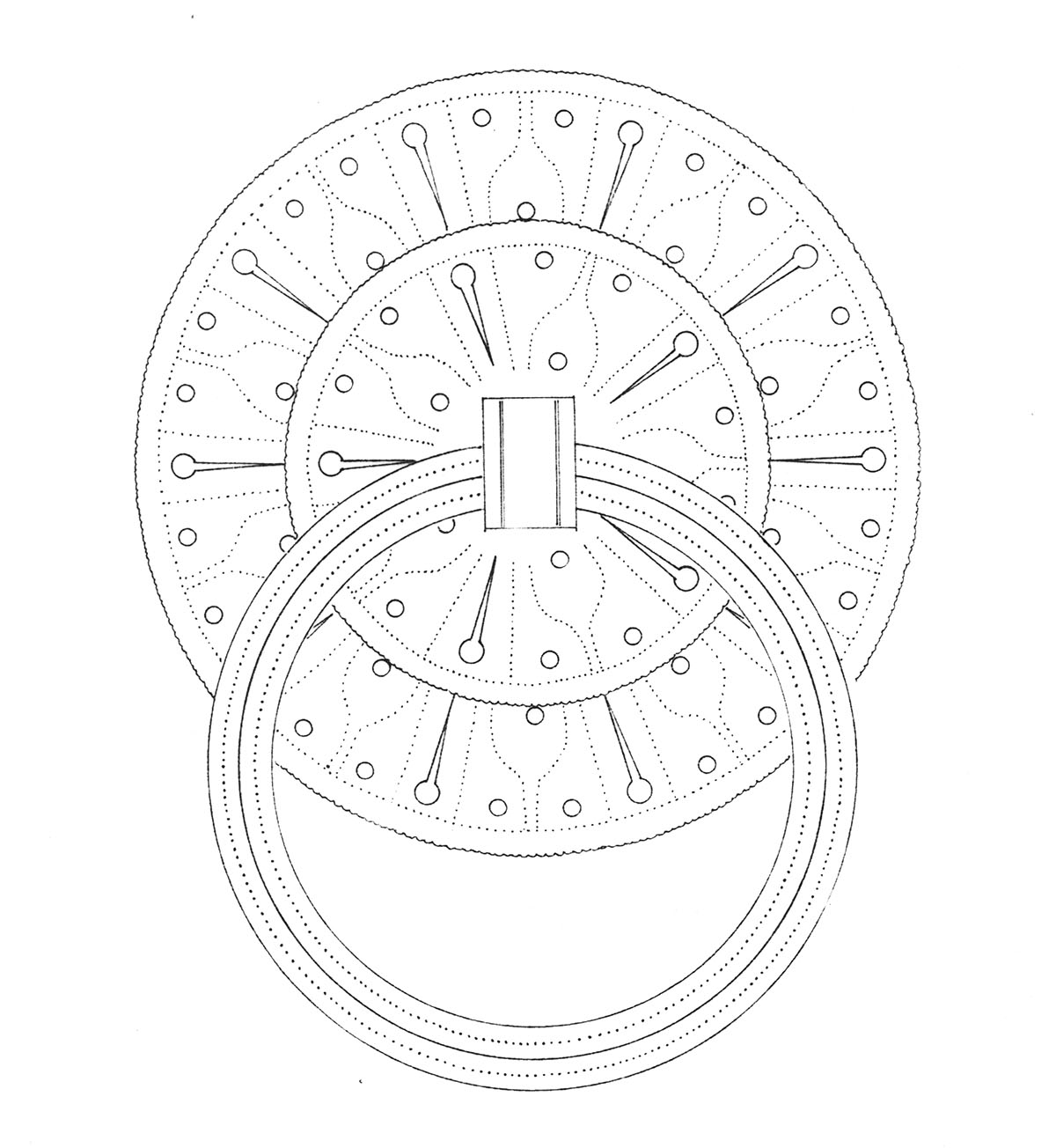

Door ring with rare decoration reminiscent of Byzantine motifs, Preveli Monastery.

On the arrival of the Venetians in the 13th century, the nobles and populace began successive rebellions against them until the 16th century. One of the conquerors’ first actions was to control iron imports, as it was a strategic raw material for swords, spears, arrows, and other weapons (the Cretans continued to be renowned archers during the medieval period). Once metals were controlled to prevent the Cretans from acquiring arms, they were also less available for other purposes, such as construction and household items. In contemporary France, Italy and Spain the opposite was true: a telling example is that fireplace fixtures in those countries were all made of iron, whereas in Crete they were nonexistent.

During the peaceful years of the 15th to the 17th century, commerce expanded and city-ports evolved into major trading centres. As economic activity flourished, so too did the use of iron. However, it was still particularly important in making knives.

Vassilios D. Kyriazopoulos, associate professor of the University of Thessaloniki, “Ironwork and Railings from Mykonos”, Zygos, Vols 10-11, September-December 1974.

From 1645 to 1897, Crete was under Turkish domination and iron imports were controlled once more as a strategic raw material.

Panelled yard door, horizontal section and outer face. 56 Nicephorou Phoca Street, Rethymnon.

Crete is a land that has been troubled by foreign occupiers for centuries. Its inhabitants never stopped fighting for survival and the preservation of their national and cultural identity on the one hand, and creating, expressing themselves, developing and conserving local tradition on the other.

Cultural heritage, the local natural environment, political and economic circumstances all give rise to solutions to the major problems of life, culminating in artistic expression, which is a way of life in itself.

The simple people who learnt to work the materials to hand and turn them into useful tools were creators. Using their own tools and inventing others, they laboured not only to construct items but to decorate and embellish them. Local craftsmen, inheritors of ancient memories, contributed to the preservation and transmission of traditional elements through their works. Their art and diligence are reflected in their harmonious and tasteful creations.

Although Cretan metalworkers did not have unlimited supplies at their disposal, they used the available materials to meet everyday needs, mainly agricultural implements and knives, which constitute a great tradition in Cretan folk art.

The use of iron in construction is limited, mainly to door and window frames (support, fastenings, handles and security) and apertures in general (ironwork). Hooks and nails are also sunk into the walls for hanging household items, vouryies (large sacks) and slaughtered animals.

The principal use of metalwork in architecture is in metal fixtures for doors and windows (hinges, struts, thumb latches and locks).

Craftsmen who made wrought-iron objects were known as halkiades (coppersmiths). In the last century, and perhaps since far earlier times, there were artisans in the towns who only made door and window fixtures, who were called (at least in the Heraklion area) kirlitzides.

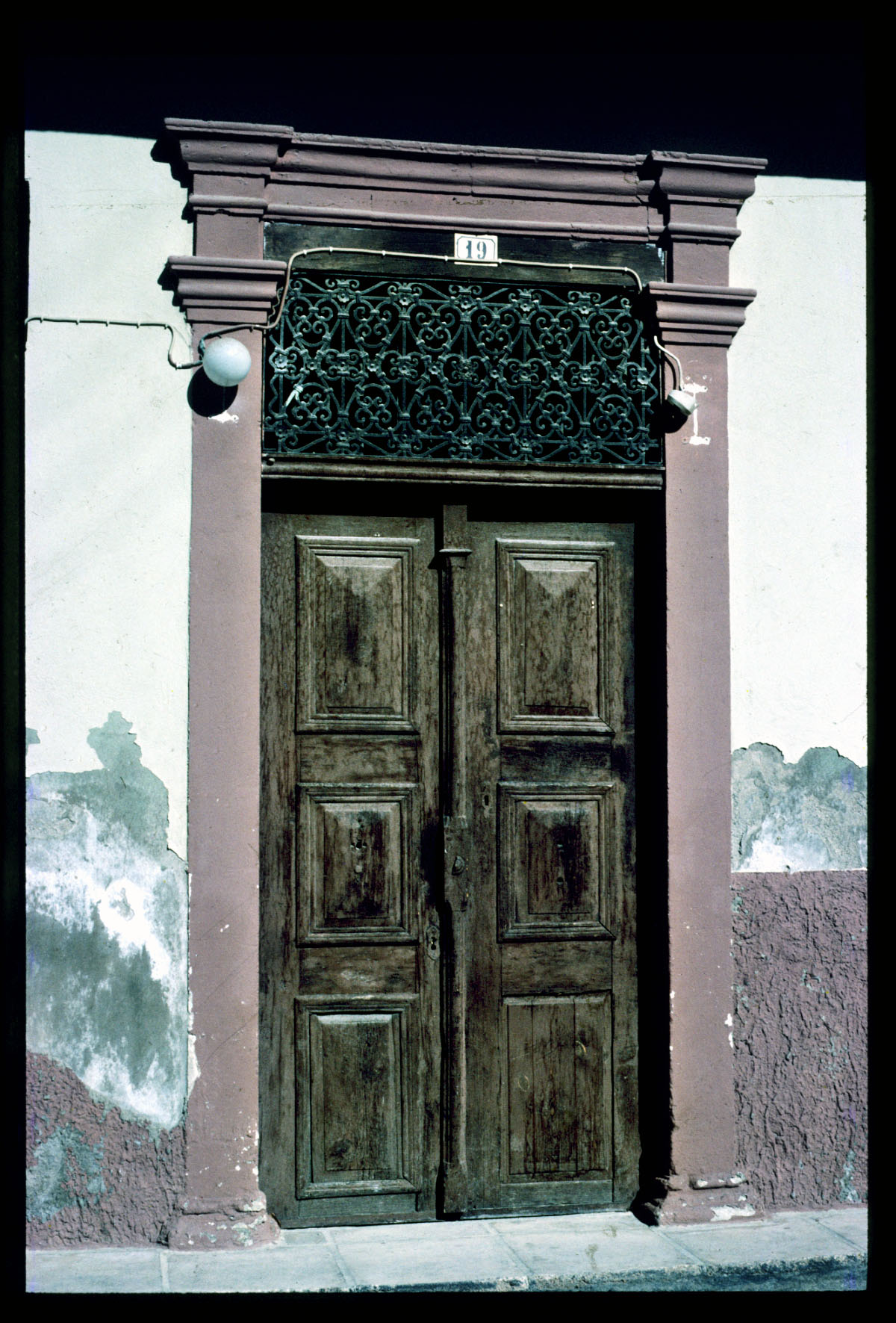

Panelled front door with grille, 19 Manouil Vernardou Street, Rethymnon.

Particular attention is paid to the craftsmanship of these small items, especially door knockers, latches and increasingly elaborate lock mechanisms. Door construction is based on the difference between the inner and outer side. The outer side and the knocker, latch and escutcheon (keyhole fitting) are all elaborately constructed. On the inner side, the fixtures are plainer and rarely decorated.

The iron is heated in the forge and beaten into the desired shape. The ornamentation (xobli) is applied by hammering and using small moulds. This must be stressed, because smiths “embroider” beautiful motifs on the iron with their heavy tools and meticulous labour.

The making and decoration of all forged items used in building are linked to the economic circumstances of every age, as well as contemporary aesthetic taste and architectural expression.

Monastery door handles and latch shapes are truly impressive. The craftsmen pour their skills and memories into these small iron objects, decorated with unmistakable Byzantine motifs.

Local artisans’ openness to other cultures and styles is transmuted by their art and craft, their inventiveness and spirit, their taste and diligence, into true artistic heirlooms.

“Nature forced the simple man to find the fundamental, the indispensable to his natural and spiritual life” (D. Pikionis).

D. Philippidis, Modern Greek Architecture, Athens 1984, p. 158 fn. 122 (D. Pikionis, Philike Hetairia 4/1925).